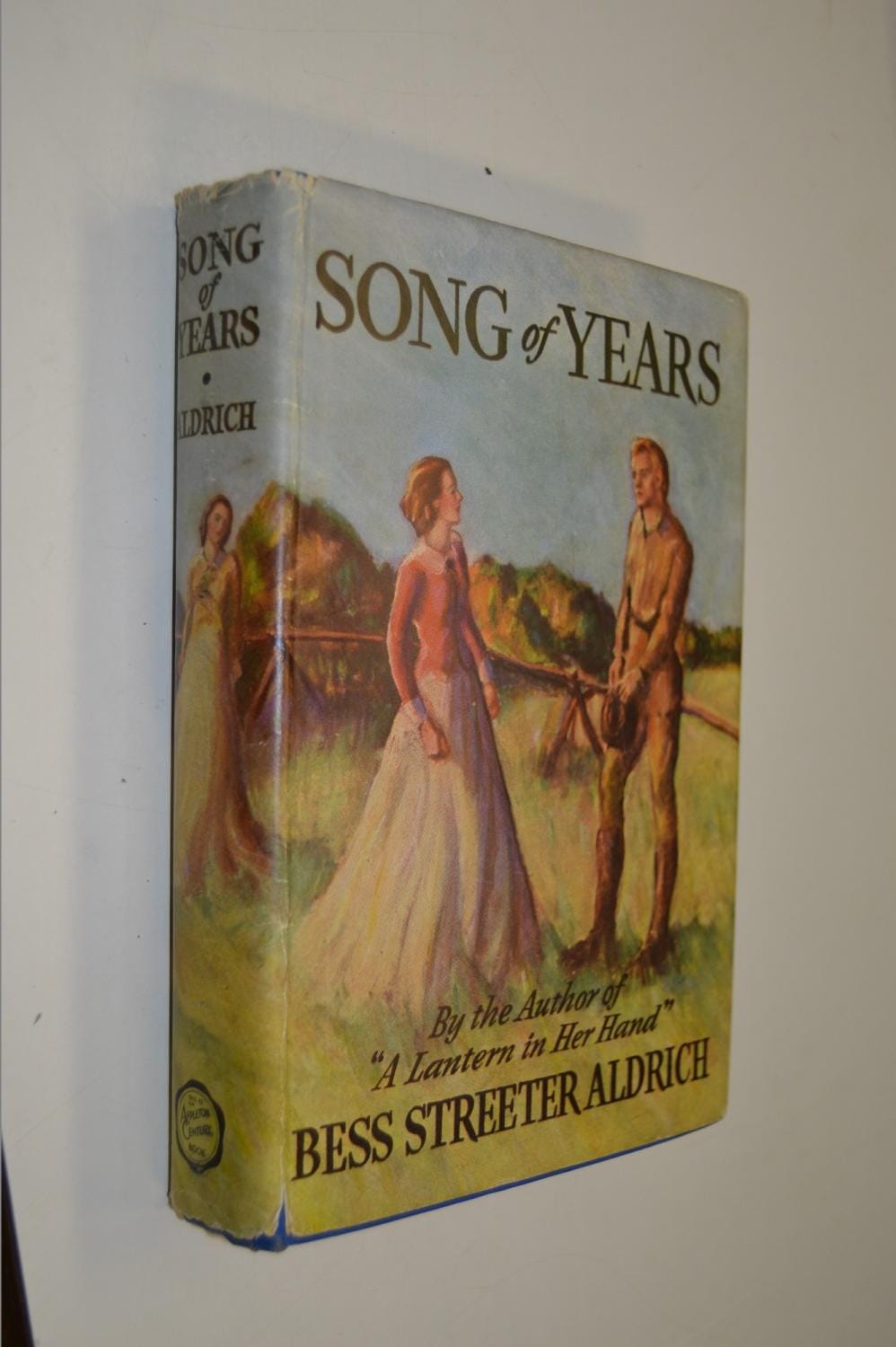

Singing a Song of Years

the rarity of love and an intense interest in life in Bess Streeter Aldrich's novel

The color of a bed of bluebells in an open patch in the timber was so beautiful it hurt you. That was another thing Celia never could understand. “Of course, it’s pretty,” she would say, “but it doesn’t hurt you. You’re touched in the head.” But Suzanne knew better. It was true, no matter what Celia said — somewhere down in your throat, their beauty hurt you. — Chapter 8

Down the road and around the corner sits an old cemetery that has been kept as a state nature preserve. We visit it often — often, at least, for two young folks who don’t know anyone buried there.

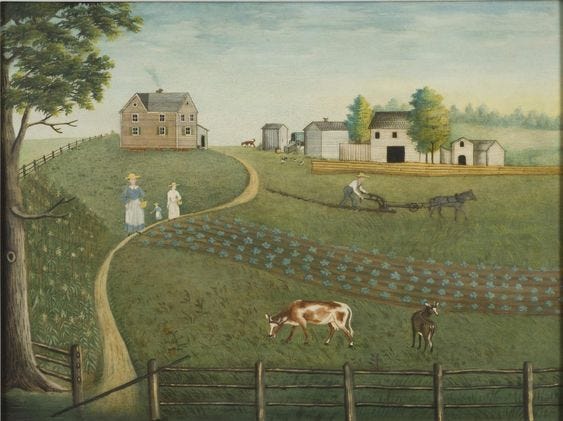

There is something about cemeteries that has always brought me comfort. Particularly this one, because it is so old. There are graves here from the 1800s, people who were born during the 1700s, whose names we can still read with a bit of effort. These are stories we will never know, but one thing needn’t be wondered: they were born, they lived, and they died. They once cooked and ate, laughed and sang, plowed and planted, and did many of the same things we do, right here on the same prairie where we make our home hundreds of years later.

I like things that remind me of that. Song of Years reminds me of that.

This book tells the same age-old story of living, working, loving, suffering, and dying. In Bess Streeter Aldrich’s lovely, vivid way, the ordinary lives of a family of pioneers are shown to be something sacred.

Like Mrs. Aldrich’s other novels, Song of Years is about a particular family and how they relate to their neighbors, the changing times, and the land itself. It’s a romance, as denoted on the back of my embarrassing large-print library copy, but the romance honestly doesn’t take up much of the 400 pages. While the romance between Suzanne Martin and Wayne Lockwood is not the most prominent part, the nature of their love was one of two distinct themes I kept noticing, running through the story like silvery threads. These were…

the rarity of love — young Wayne Lockwood holds out for the “girl in the cloud” of his dreams. To him, settling down with any woman who happens to be available, simply to cook his meals and clean his cabin and lay beside him at night, while practical, is not enough.

and…

the intense interest of everyday life — the Martin family approaches life with a feverish vitality, finding amusement in homespun activities and even work. The intensely human matters of love, friendship, gossip, scandal, and community are the most exciting things in life.

I have loved Mrs. Aldrich’s writing ever since I first read A Lantern in Her Hand in high school.1 I love her trademark tendency of using the same refrains over and over again throughout her novels. Remember Isabelle Anders-McKenzie’s “long fingers that taper at the ends,” or Old Oscar Lutz’s “pail with a rope for the handle”? I will always remember the words of old Abbie Deal in A Lantern in Her Hand, “and then Willie Deal came walking down the lane.”

Song of Years opens in a cemetery somewhere on the plains of Iowa, which could have looked much the same as the one I have frequented of the years. Headstones in this cemetery are carved with the names of seven daughters of the same family, followed by beloved wife of — and the men with whom they made their homes. These names the reader doesn’t know yet, but in a way, this is our introduction. A fabulous way to begin a novel, if you ask me. It’s no spoiler, because we know they will all die. Now let’s see how it was they lived.

Jeremiah Martin is the patriarch of the family of settlers who live in the sturdy white-washed cabin off the lane road, with the stake-and-rider fence and the lean-to and the hollyhocks growing up near the house. His natural inclination towards lively discussion and his passion for getting things done end up landing him in the new state legislature. A lot is happening for Iowa in these early years, and a lot is happening in the country as a whole. Northern and southern sentiments are at odds, and soon enough war breaks out and takes many of the young settlers to fight. It takes old Jeremiah as well, for a singularly important job that only he can do.

Jeremiah has two sons, quiet Henry and dashing Phineas, and seven daughters — Sabina, Emily, Jeanie, Phoebe Lou, Melinda, Celia, and Suzanne.

Wayne Lockwood is a fresh-faced, hard-bodied (as we are often reminded, thanks Mrs. Aldrich) bright-eyed young man from New England with a classic American Dream. He arrives in the fresh new country between the little towns of Sturgis Falls and Prairie Rapids to set up his own farm, and soon has a fine little operation going with a tidy cabin and a large flock of sheep.

Working in the soil and with the animals he was a part of Nature herself. He knew the urge of groping, growing things, the force that drove the mating, the mellow feel of Nature at the seeding and the satisfaction of the harvest. — Chapter 23

People ask Wayne about getting married, but he shakes off their comments. He knows it would be practical to just pick a girl, but he’s embarrassed to admit to anyone that to make him want to marry a girl, he would have to be very much in love with her. The “girl in the cloud” of his dreams seems to be only that — a dream. But he holds out hope, living his bachelor life and making friends with just about everybody.

Suzanne Martin is the youngest of the sisters, just a girl when Wayne arrives. He is enthusiastically accepted into their circle of friends, and the girls tease each other about who will “set her cap at him”. Suzanne is always caught between her make-believe dream world, where everything is beautiful and sacred and private and made-up, and the real world, where she teases her sisters and helps her mother. She notices to her surprise that Wayne seems to be able to cross into that dream world with her. Even as she decides that none of her sisters, including herself, are worthy of him, she knows she will never love anyone else in the same way.

There is a whole tribe of women in literature who have bound themselves to a love like this, suffered the trial of it, and oftentimes never reach the satisfaction of being noticed and loved in return. (Molly Gibson from Elizabeth Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters and Eponine of Les Misérables renown come to mind.) Personally, I can be torn between thinking, give him up, he’s not worth it! and alternately applauding such devotion to man who doesn’t return the woman’s love, who may even be in pursuit of another.

Suzanne, after coming into her womanly maturity, tries very hard to keep Wayne out of the private sphere where her dreams live. When it gets too difficult, she gives up and resigns herself to go on loving him quietly and fiercely. To Wayne, Suzanne is first a child, then a friend. Never does she strike him as the “girl in the cloud” for whom he waits…at least, not for a very long time. Eventually, he realizes that the girl in the cloud isn’t real, and isn’t going to magically appear. Suzanne is the most real, most secure, and most wonderful person in the world to him, the very kind of woman he’s been longing for for so long. Sometimes, these things take a war to get rolling.

There is much to be said for marriage brought out of necessity, and the kind of love that grows out of a sacred covenant. There is also an admirable honesty in a good man in search of a wife simply because…he needs a wife. This is one of the things I love about books like Sarah, Plain and Tall by Sarah McLachlan. There is no spark that prompts Sarah and Jacob to get married, at first. It is because he needs a wife to care for his children, and she is society’s perfect example of an old maid who has nothing to lose. Strong, enduring love does not always begin with dreams of romance.

However. I could see my own past dreams of love in Wayne’s position, surprisingly, and I appreciated the different perspective. He wants a woman he can’t live without and knows he should wait until she presents herself. To marry a nice prairie daughter that he didn’t love in such a way would be unfair to her. In this way, Wayne is more of a romantic than Suzanne. She simply sees Wayne once and loves him, and doesn’t ever go back on what has been firmly decided in her heart.

I have a distinct, turning-point memory of talking with a missionary’s wife at a friend’s house several years ago. I was in a very new relationship with someone I deeply cared about, in the way that friends do, but something was not right. I wondered whether it was love of a marriage caliber.

The missionary’s wife was asking me about him. She then began talking about her own husband and when they met, and how they fell in love. I watched her face and listened to how she spoke about her husband. In that moment I knew I wasn’t in love, and I knew it would have to end.

That missionary’s wife reminded me of something I wasn’t willing to give up. It was the love that Wayne Lockwood knows must be out there somewhere, and I wasn’t ready for it until another year down the road. Love is not rare in that it doesn’t happen to many people. But it is exclusive, and the soul-deep connection of a marriage is precious because it is just the two of us. It could be no one else.

Inside there was the never-ending procession of daily tasks — baking, cooking, washing, ironing, sewing, scrubbing. But the settlers’ interest in life did not cease with these. With the hard work went a capacity for enjoying their pleasures to the full, for sympathizing with a suffering neighbor, for grasping at knowledge of outside human affairs hungrily, for soaring to exultant heights and groveling in miserable depths. Humanity remains much the same. Only the setting and the times change. “I love you” spoken in whatever tongue or generation springs from the same rapturous feeling. “He is dead” brings the same black despair. — Chapter 11

With a father like Jeremiah Martin, it’s no wonder his family grows up with a large appetite — an appetite for news, for pleasures, for humor, and for change. When Wayne comes to the Martin’s home for dinner on his first night, the thing that strikes him is how lively everyone is. He’s never seen such lively girls! Not girls, he thinks to himself — just people. And indeed, if there is amusement to be found in anything, these girls will find it.

The settlers’ lives on a macro level revolve around the changing seasons, weddings, births, holidays. On a micro level, it’s the scrubbing, baking, preserving of food, and mending of clothes. Yet, these things aren’t seen as menial or something to be hurried through to get to the next big thing (unless, of course, there’s a dance being held that night at the Overman Hall). All of it is part of life.

When Phoebe Lou marries Ed Armitage on the spot to follow him to Colorado, the letters she sends back to her family are treated like treasures and savored. Suzanne and Celia spend their girlhood days in summer picking wild berries and swinging on wild grape-vine swings, and it’s the most fun thing in the world. Entertainment in this landscape is homemade because it has to be, and so much more precious because it is.

While I was thinking about this, I recently read this excellent article by Alissa Bonnell on her Substack Divine Nature. She emphasizes the value of “the homemade life.” Her words ring true, and it’s heartening to know I am not the only one who still believes in (and longs for) a more homespun life.

Home, work, leisure, fun. These are old words, and they mean the same thing now as they ever did. In Song of Years, the Martin’s home is the center of much of their lives, and I loved that. The necessary activities of life in the 1850s, like gathering and preserving food, are best done in company of others. Oftentimes they need to be done so. This fosters human interaction, which encourages creativity, which enriches life.

It’s easy to romanticize the past. I am fully aware that I do it all the time. I decorate our home with 19th century details because it’s romantic to me, and I light candles to resist the stranglehold of modernity.2 These are only preferences, of course. But I do believe there are qualities of a more primitive life that are indeed better for us as human beings. Creating your own entertainment is almost a lost art in a world of screens and endless media, where moderation doesn’t seem to exist. Interacting with other human beings brings endless rewards, much richer than time spent in the seclusion of a virtual world.

I want to tell the world that it’s not lesser simply because it’s old-fashioned! It’s not lesser to be interested in the lives of your own close neighbors, or to find great excitement in things like the agrarian seasons. These are the things of life, and always have been. How can what is good for humans suddenly become opposite of what always was?

Suzanne and her sisters feel overwhelming excitement about things like parties and news from their father in the legislature, and also things like when the maple trees are ready to be tapped and when the wild blackberries are ripe. Laura Ingalls Wilder puts it well, that “it is the sweet, simple things in life which are the real ones after all.”

All these crowded now into the new cabin with their baskets containing the party refreshments and donations toward Wayne’s housekeeping. The Martins had brought some butter and lard and a stone crock of fresh strawberry jam. The two families of Akins had two live hens and a rooster for him, and a sack of new potatoes. The Mansons had only some cornmeal which they offered with apologies but which Wayne sensed had been a generous gift. ….the little cabin was filled with them, 26 adults and children besides. “You will be lonely and friendless out there,” Wayne’s mother had argued. — Chapter 7

This book gives the reader an almost cinematic feel, like watching an old historical movie. A sweeping orchestral score seems to play in the background throughout. There is a lot of historical detail, noteworthy events cataloged and names mentioned, and the lengths of research the author must have gone to are truly impressive. Mrs. Aldrich is known for her historical accuracy, so I’m sure it’s a pretty good timeline of what really happened in Iowa in the 1850s and 60s leading up to the Civil War.

If there is any one character whose spirit stands out the most, it’s Jeremiah Martin. I haven’t undertaken to talk much about his merits at the moment, but he really is the glue that holds the story together. His enduring advice to his family of sons and daughters, and to all those he influences in the young country, is that whatever happens in life, the response must be to “pull on through.” Simple, somewhat broad, but solid advice from an old man who has done just that.

“Now, Ma, you moved out here with me.”

“Yes, and sometimes I think more’s the pity we come. At least I had stairs back in York State.”

“Why, Ma, you and me will be climbin’ the golden stairs together some day.” He laughed long and heartily at the thought. “Then you’ll feel foolish you made such a fuss about any other kind.” — Chapter 21

At the book’s end, we find ourselves back in the little cemetery later on in the 19th century. It’s now overgrown, a little crumbling, and there are more names etched in stone. The seven Martin sisters, married and become mothers (all but Emily, bless her heart) have made their mark on the Iowa prairie and are laid to rest with their parents, living on as memories. We have come full circle.

What a sweet, light-hearted but profound book. Well done, Mrs. Aldrich. I also highly recommend her novels A Lantern In Her Hand, A White Bird Flying, and Spring Came on Forever.

“By granny!” He was thoughtful. “I will be deader than a doornail, won’t I? Funny, how you just can’t believe that you won’t live always and see how the new state and the country and everything pulls through….Why, did you children ever stop to think you can’t do away completely with anything? That fiddle of Phineas’ was once a tree — wind makin’ music in the top of it. Cut down that there maple tree outside the lean-to door, burn the trunk to ashes, and Ma’ll up and leach the ashes for lye. Scatter the leaves and they’ll make winter mulchin’. Seeds that have been shook off will come up. No, sir, if you can’t kill that old maple you ain’t goin’ to be able to kill me. I’ll be in somethin’ a hundred years from now, even if it’s just the prairie grass or the winds in the timber or the wild geese ridin’ out the storm.”

— Jeremiah Martin, Song of Years

In reading more about her, I learned Bess Streeter Aldrich was the mother of four children and a widow for much of their childhood. She wrote her books and magazine stories in between taking care of the house her children, and she put them all through college with the money from her writing. And here am I, complaining of not enough time to write!

And I wear dresses because it’s easier to imagine oneself as Claire Fraser gathering medicinal herbs from the laird’s castle gardens when you’re wearing a long skirt than when you’re in jeans.

I recently read Gap Creek, as per your recommendation on a recent post. When Ma Harmon said that love is “a lot of hard work, just like anything else,” it was so impactful for me. Bess Streeter Aldrich’s masterful novels had a similar effect for me as Gap Creek. She writes about multigenerational families who live, grow, and die through the hardships related to the land— not in spite of them. Reading these pieces set around the turn of the 20th century, including Robert Morgan’s novel, I think it’s safe to say the “work-life balance” is a modern idea. Trying to compartmentalize our family life and our back-breaking work is a lot like trying to have satisfying marriage separate from self-sacrifice. It’s like trying to grow healthy crops without having dead and teeming things in the soil. It’s ugly and it’s fake. It’s divorcing two things that belong together.

Your take on Singing a Song of Years made me think that proper “work-play balance” may be a more appropriate goal. Because all of it is life. While tasks we complete every day are difficult and of eternal significance, some of them should still be pleasant, restful, and dare I say fun? Thank you, Ms. Emma, for the wonderful write.

I just finished finally reading SONG OF YEARS, after all three of my siblings had read it and raved about it and told me I was sure to like it (and they were right). You've captured all the best things about it so beautifully here.

It's interesting too your noting Aldrich's "refrains" and the cinematic feel, because I was also just thinking how beautifully she uses what John Truby calls a "symbol web," the visual and thematic motifs repeated throughout the story—Wayne's singing, the gate with the horseshoes, lighted windows, the Seth Thomas clock, the wildflowers and wild fowl in the slough, the family gathering for meals, and the keepsakes and hand-me-downs like the green parasol and the artificial cherries. And the recurring theme of determined journeys, on foot, horseback, by wagon, stage, and finally train, and then circling back to foot again.