“We go together like peas and carrots.” - Forrest Gump

The questions of life tend to come to me in the field. Not the literal field, per se, as in a field of hay or grain, but the metaphorical field of my vocation — the farmer’s field, where work is done and life is observed. If I forget my notebook, as I did on our walk today, I end up scolding myself. I try to capture the many thoughts that come to my mind until I can plant them properly and let them grow.

They could be little things — why do beautiful plants have ugly names, like mugwort and fleabane? Sometimes they are big questions — how does loving people translate to caring for nature, and isn’t that the end goal of conservation anyway? Or perhaps they are questions of how to best care for my animals, or how to arrange this plot of soil in the smartest way for succession planting. Farming is full of questions. Sometimes the answers are fairly simple and earthy, and other times they bounce around the atmosphere and echo in the trees and the clouds, and I can’t quite catch them. They are answers I would love to know, and pray for, and wait to see, however long it might take.

But it’s not always questions. Farming is also rich with stories, and sometimes that is where the answers lie.

Have you ever noticed how common it is that farmers are also writers? I notice this more and more. Not all good farmers are writers, or good writers. Perhaps the best farmers I know are not writers at all, and maybe this helps to focus their devotion. I am not a great writer yet, nor a great farmer, but I have thoughtfully devoted myself to both as high callings and worthy vocations, and I have been frankly delighted to discover how naturally the two things fit together.

Sometimes people are drawn to pursuits that exist in conflict with one another — for example, I used to dream of being a folk singer and traveling around the country, but I knew I wanted a family, to homeschool our children, and to grow lots of food. A person could attain a high-paying, prestigious job in a big city, even one where they can do a lot of good, but the greater pull toward a life lived close to the land and together with their family might make having both things impossible.

I feel a little like this sometimes, when my day job takes me to the city and I find myself in a 22nd-story room for many hours, moving only the muscles in my hands and filling my mind with the troubles of other people’s lives. This kind of a routine would not be compatible or sustainable with our family dreams and goals, and that is why I have every intention of giving up the one thing in order to feed the other.

Farming and writing, on the other hand, are as beautifully compatible as peas and carrots. I think this is because the good farmer, just like the good writer, is tasked to be an observer. The farmer walks his land and observes the animals, the grass, the moisture, the rise and fall, the life and death. And then, if he is a writer, he can’t stop there, but must also tell about it.

The cycles of nature and seasons afford convenient opportunities to be a farmer in fair weather and a writer in rain. Life is either bursting with fullness, with one hundred and ten tasks to complete before the first frost, or it is absorbed with the fullness of the busy times, and this spills over into words that show the colors, smells, shapes, and sounds of that abundance. Maybe farmers become writers because there is too much of life to contain, and maybe writers become farmers because there are no processes so beautiful as those of living things, and therefore no subject quite as captivating upon which to dwell.

I have been heavily influenced by Wendell Berry. I’d guess for most people, when they think of a literary farmer, Berry is the first to come to mind. There have been times when I’ve so immersed myself in his writing that I feel I have to be careful not to say things he has already said. But then, maybe it’s because he has already voiced something that I feel emboldened to repeat it, and in that way I join in the greater chorus.

Farmers who write compound their impact. In a time when farming wisdom is a rarity, it is a gift for the young farmer to have books when he might not have a mentor. Gene Logsdon is another farm from whom I’ve delighted to learn. It seems appropriate that it should take a writer’s mind to notice, catalogue, and detail the various species of pasture grasses found here in the Midwest. Berry and Logsdon, along with Joel Salatin, Kristin Kimball, James Rebanks, and Lynn R. Miller have all offered to me — and to you — the wealth of their experience in their words. And not only experience, but love, too, the value of which is immeasurable.

I didn’t think I needed to learn to love farming, and maybe I didn’t. But I have needed, and do still need, to learn how to be a good farmer. Some of it is intuitive, but even intuition needs waking up sometimes. There are a million things I don’t know that I might need to one day, things my life will be richer or having learned.

In the same way, there was never a time I didn’t love writing, or that I didn’t carry the urge to tell stories about everything I come across. But writing and storytelling is a discipline, too, and requires honing. Farming, with its necessary observance, feeds my craft, as it does my soul and my body.

I think of Mary Oliver’s “instructions for life” —

“Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.”

That is the life of the literary farmer. Simple enough, far from dull, not always easy, but as rewarding a life as I can think of.

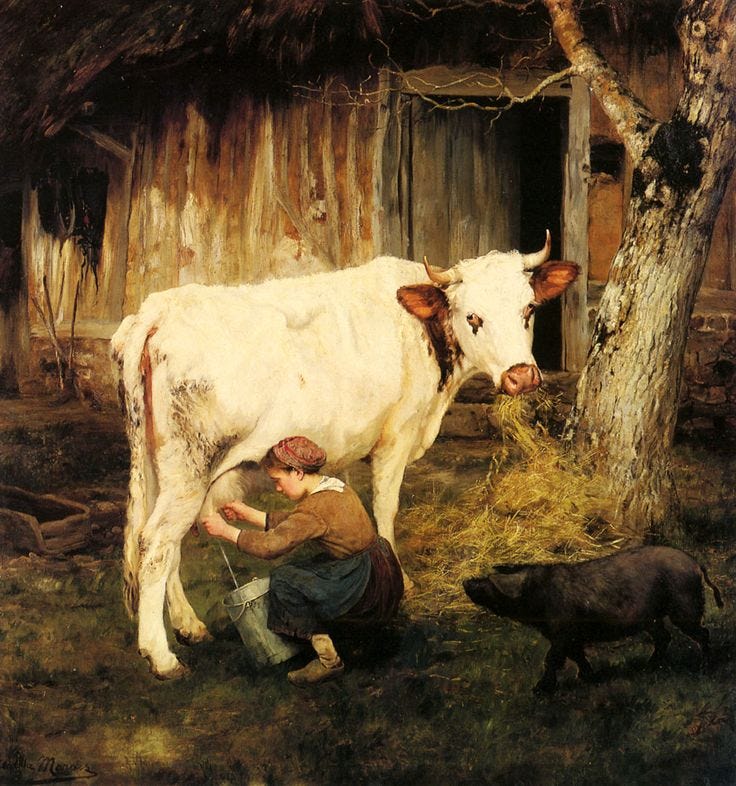

I have a young friend, half my age, who does this well. She is an observer, and this makes her a good farmer. She notices behavior in her cows that tells her what they need, hearing what they say just as if they could talk to her. She remembers everything she has ever heard or seen and has it filed away until it might be useful. She pays close attention, and she lets herself be astonished. She and I get along together like peas and carrots, and she inspires me to pay close attention, too.

When I do pay attention, what follows is the natural result of being a writer: I must tell about it. And in telling, I can rest for a spell from my physical labors. When the telling is done, and the clouds have cleared, it’s 5 o’clock, and it’s chore time once again. And so the dance continues in a comfortable, compatible rightness that feels, in a world of conflicting desires, like hope.

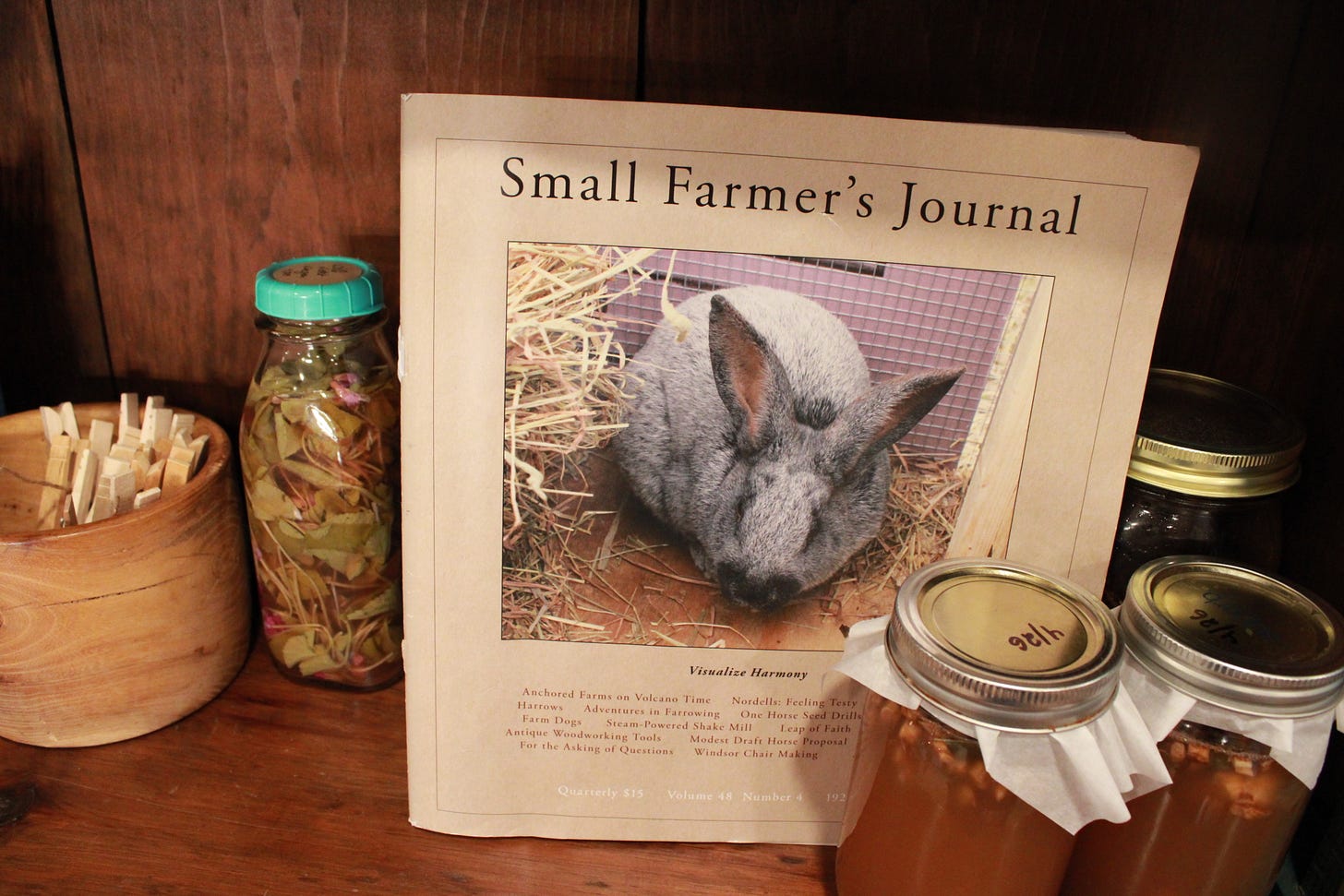

My first article in print arrived in the mailbox this week! I’m thrilled and honored to be featured in the latest issue of Small Farmer's Journal. Such a lovely magazine that I highly recommend.

I told Pierre the rabbit that people all over the world are reading about him. All he did was sniff, wiggle his ears, and hop away. He is modest, and I guess I am less so. My heart leapt to see my words in print for the first time. Such a special thing!

“The time is right to mix sentences with dirt and the sun with punctuation and rain with verbs.” - Richard Brautigan